There has been a great debate over the military action in Libya by several Western governments, supported by some Arab governments. The central question has been: by what right are these governments intervening in the internal affairs of a state?

Some context is necessary for the intervention that has been authorised by the UN Security Council.

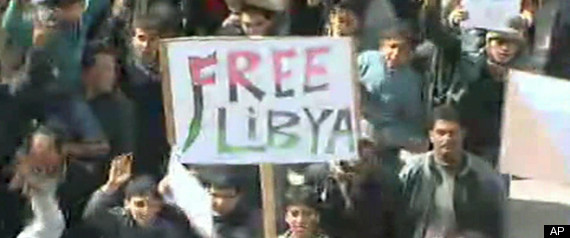

An uprising in Libya against its tyrannical leader Muammar Gaddafi came in the wake of similar rebellions against the autocratic leaders of Tunisia and Egypt. It coincided with what appeared to be a sweeping movement in Yemen, Bahrain and Syria which have now experienced unrest by large numbers of people who want regime change and greater freedom in their societies.

When the rebellion in Libya started, Gaddafi was merciless in using the military to try to stifle it. He even recruited mercenaries from African states in the event that, as had occurred in Egypt, the military showed reluctance to use violence against their own people. Many hundreds were killed from the very outset. While the blood of Libyan people was being spilt, the world was treated to the farce on television of Gaddafi declaring: “My people love me. My people, they love me”. Gaddafi then went on to claim that the unrest was created by al Qaida. He did not claim that it was fomented by Western nations, nor did he assert that the uprising was the work of Western oil companies intent on seizing Libyan oil.

Apologists for Gaddafi, and those who benefit from his financial help, close their eyes to decades of despotic rule, brutal human rights abuses, repression of dissent and murderous adventures in other countries. In trying to stamp out this rebellion he set upon the populations of Brega and Zawiya and terrorized the people of Misrata including by using military planes to bomb them.

Members of both the Arab League and the African Union expressed great alarm at the extent of force used by Gaddafi and they joined Western states at the United Nations to call for action to try to stop him. On 27 February the UN Security Council agreed Resolution 1970 which condemned the actions of the Libyan authorities, demanded an end to violence, access for international human rights monitors and the lifting of restrictions on the media.

As the situation continued to deteriorate with more civilians being killed and Gaddafi’s failure to comply with Resolution 1970, the Security Council met again and on 18 March adopted Resolution 1973 which called for an immediate ceasefire and authorised “all necessary measures to protect civilians” including the imposition of a no-fly zone. It did exclude a foreign occupation force in Libya.

Resolution 1973 was supported by 10 members of the Security Council with 5 others abstaining. The 5 countries that abstained were China, Russia, India, Brazil and Germany. Under Article 27 of the UN Charter, decisions of the Security Council have to be made by an affirmative vote of nine members including the concurring votes of the permanent members. In this case, 3 permanent members concurred and 2 did not. But, none of the permanent members cast a veto which could have blocked the resolution, and since an abstention is neither an affirmative nor a negative vote, it is not sufficient to prevent action. All the permanent members would be aware of this procedure, therefore it has to be assumed that Russia and China – the two permanent members that abstained, but did not cast a veto, had decided it was in their interest not to oppose the Resolution.

What was behind the Resolution and what further validates the intervention in Libya is a decision taken by representatives of all governments at the 2005 World Summit. Governments agreed that where an individual state subjects its people to genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, the international community has “the responsibility to act”, and “in this context”, to take collective action, in a timely and decisive manner, through the Security Council “should peaceful means be inadequate and national authorities manifestly fail to protect their populations”.

By his own actions of choosing to respond to the unrest by violence and killing, Gaddafi set the stage for the intervention that followed based both on the UN Charter and the decision of the 2005 World Summit on the international community’s “responsibility to protect” people whose own state turns on them.

At the time of writing, it is by no means clear how events in Libya will end. Gaddafi and his ruling clique have shown no willingness to engage the dissenters in a dialogue; if anything they have intensified their military offensive. Meantime, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) has been given leadership of the UN Security Council resolution to enforce a no-fly zone and to protect the lives of civilians. Without committing ground troops themselves in aid of the poorly-armed and militarily-untrained rebels, the most that NATO can hope for is the isolation of the Gaddafi regime and its eventual collapse.

What was the alternative? US President Obama summed it up on March 28 in an address to the American people when he told them: “There will be times when our safety is not directly threatened, but our interests and our values are. Sometimes, the course of history poses challenges that threaten our common humanity and our common security -– responding to natural disasters, for example; or preventing genocide and keeping the peace; ensuring regional security, and maintaining the flow of commerce. These may not be America’s problems alone, but they are important to us. They’re problems worth solving”.

Obama’s words to the American people hold validity for people all over the world who cherish freedom and uphold the values of human and civil rights. The world has shrunk in many ways through air travel, instant communication, interaction between civil society organisations, and a growing sense that mankind inhabits one planet. Only autocratic regimes still cling to the notion that ruling regimes must act brutally against their own people to keep themselves in power.

The “responsibility to protect” proclaimed by the World’s leaders in 2005 – whether all of them meant it or not – is now a principle whose time shows every sign of having arrived and which a conscientious Security Council should uphold whenever it is clearly necessary.